Is this the TRUE face of the man who made the world go round?

Scientists rebuild Copernicus’ likeness from his skull

The astronomer toppled received wisdom when he proposed that the planets orbit the Sun, rather than the Earth, and that Earth spins on its axis.

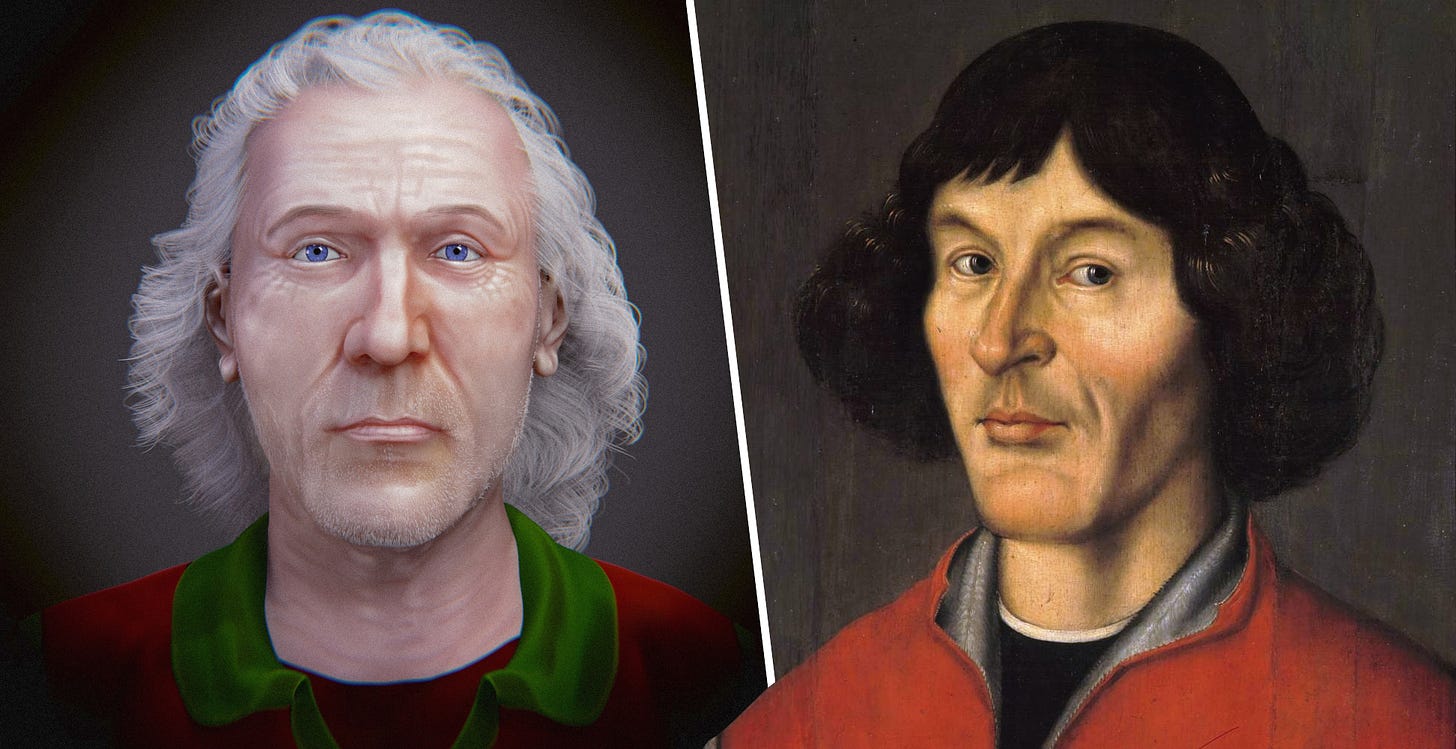

Yet for all his influence, no portraits of him survive from his lifetime – a self-portrait was destroyed by fire in 1597 – and only depictions based on that portrait remain.

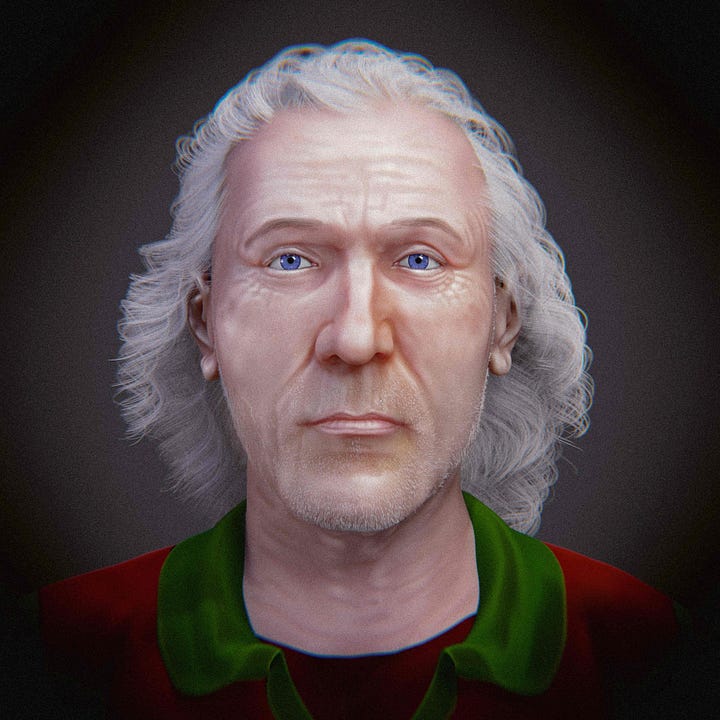

Now the face of Nicolaus Copernicus can be seen for the first time since the 16th century, after scientists reconstructed his features using what’s thought to be his skull.

Cicero Moraes, author of the new study, said: “A problem involving historical figures is knowing whether the portraits that come down to the present day are compatible with the individual in life.

“In the case of Copernicus, as far as I studied there is no intact portrait that was painted during his lifetime.

“Those that are available are posthumous, perhaps copies of contemporary originals – unfortunately the data related to them is not clear.

“However, the reconstruction was significantly compatible with the portrait that is best known of the astronomer which was painted around 1580.

“This does not prove anything, but it is a fact that they look similar; it can just be a coincidence, but it occurred.”

The remains on which Mr Moraes’ reconstruction was based, were found by archaeologist Jerzy Gąssowski and his team under Frombork Cathedral, Poland, in 2005.

It was there that Copernicus wrote his masterwork, De revolutionibus orbium cœlestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres), and it’s also where he died and was buried.

Hairs taken from a book belonging to Copernicus were a DNA match with the remains, and Gąssowski said he was “almost 100 percent sure” it was the man himself.

But just like the astronomer, the discovery wasn’t without controversy – with some experts questioning whether it was the real deal.

It was this debate that inspired Mr Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert prolific in the field of forensic facial reconstructions, to give the body a face.

He said: “I was very interested in the debate surrounding the discovery of the remains attributed to Copernicus.

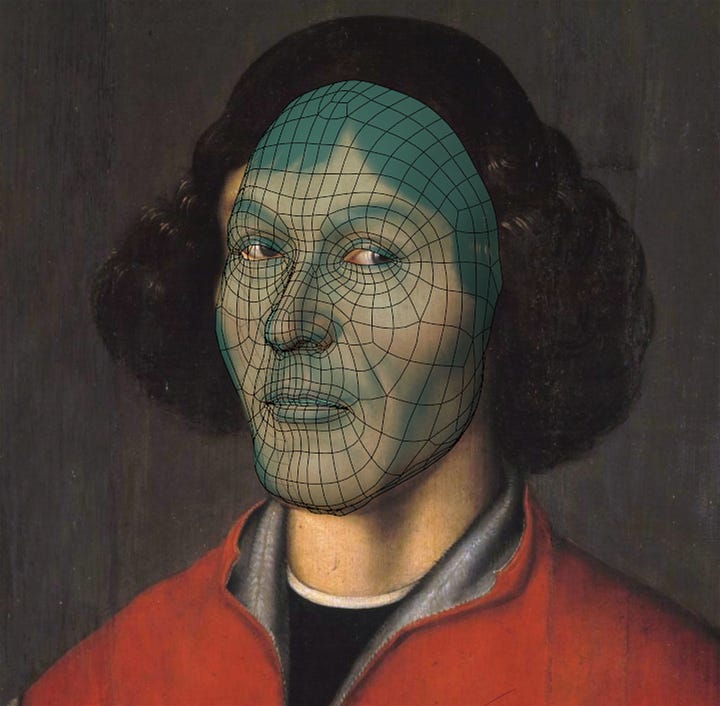

“The basis for facial approximation were images with volumetric references, available in academic articles and journalistic news.

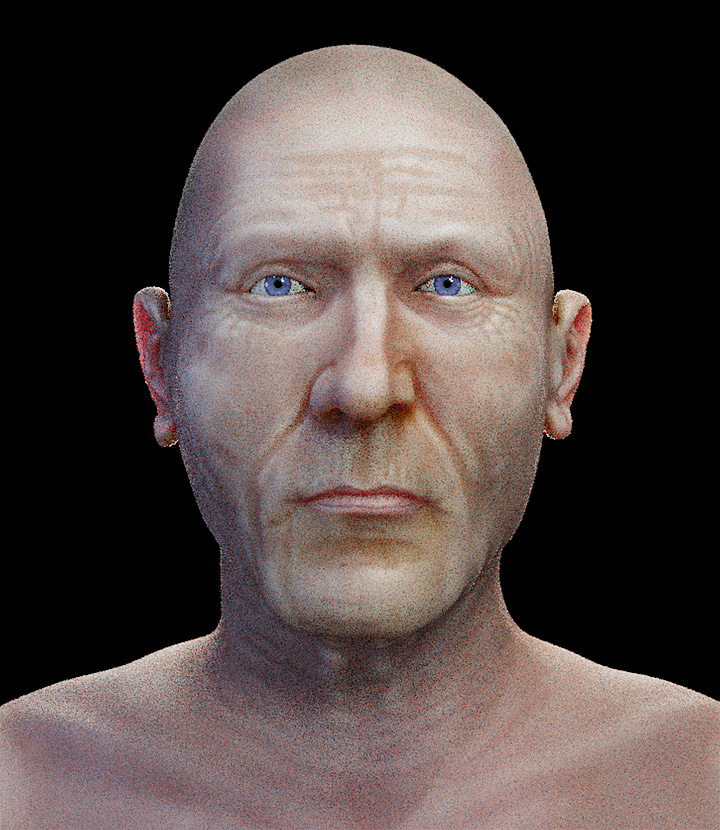

“The skeleton found is not complete – in the case of the skull, the mandible was missing.

“This required a projection based on computed tomography data to reconstruct it and proceed with the facial approximation.”

He continued: “Once I reconstructed the complete skull, I proceeded with the facial approximation.

“This consisted of using data extracted from measurements on living individuals to arrive at a face that could be compatible with the worked skull.”

Mr Moraes said the final result was a “serene” face, showing the astronomer as he appeared at the time of his death, aged 70, in 1543.

Copernicus was born in what is now Toruń, Poland, in 1473.

He was a Catholic canon in his lifetime, and his heliocentric astronomical model was initially accepted by the church.

But that changed after his death, and his works were added to a list of books banned by the Catholic church in 1616.

Cicero published his study in the 3D computer graphics journal OrtogOnLineMag.