Face of 'only Egyptian pharaoh to die in battle' REVEALED

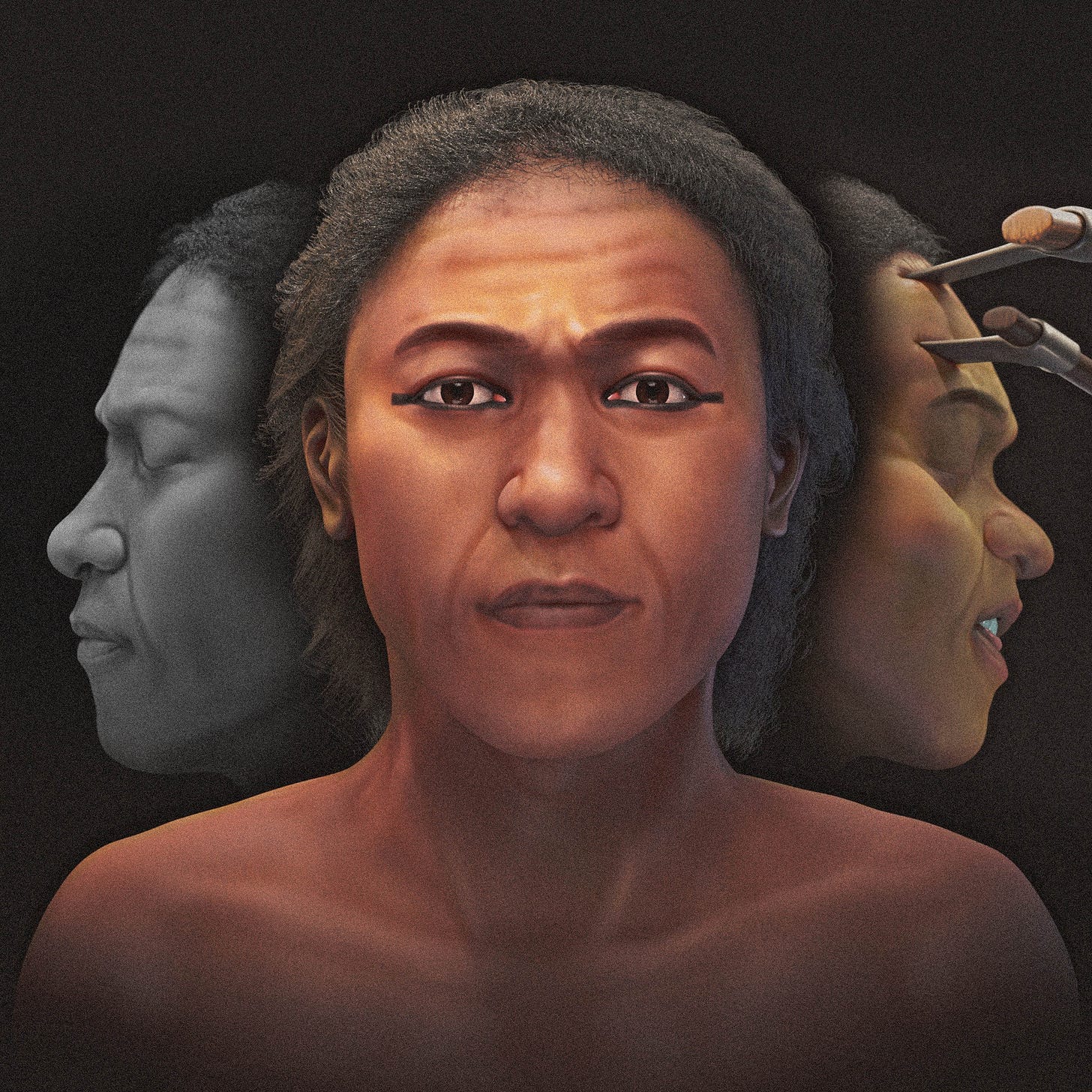

Scientists rebuild likeness of 'freedom fighter' mummy – complete with the axes that killed him

THE face of the only pharaoh to have died in battle can be seen for the first time in 3,500 years, after experts reconstructed his likeness – complete with the axes that killed him.

Seqenenre Tao ruled in the 16th century BC, at a time when Egypt was partially occupied by the Hyksos people, and his reign was marked by conflict with the invaders.

He’s been called a “freedom fighter” who died trying to liberate Egypt, and whose heir would ultimately succeed in doing so, but his face was lost to history.

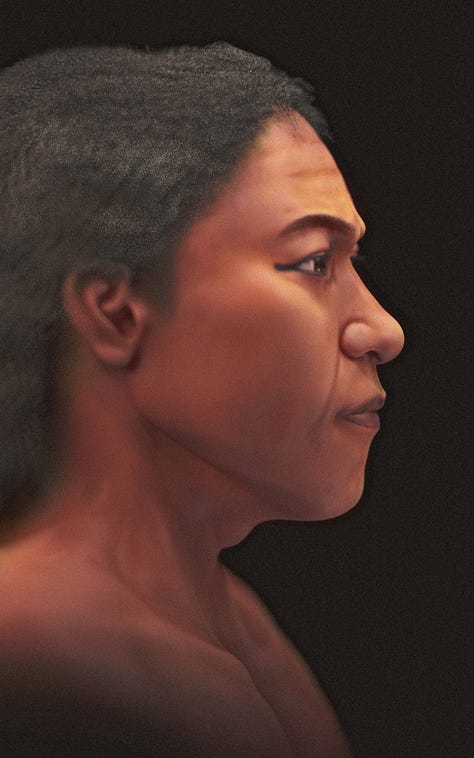

Now, using his mummified remains, experts have reconstructed his appearance as it was when he was brutally cut down at roughly 40 years of age.

Michael Habicht, an archaeologist at Flinders University in Australia, said his mummy was visibly different from those of other pharaohs.

He said: “What draws attention to Seqenenre's mummy is the position of the arms and the appearance of the face.

“It is speculated that he died in battle and underwent the mummification process days after his death, or an ad-hoc mummification near the battlefield.

“The embalmers did the best job possible, but Seqenenre’s image differs greatly from other royal mummies, who rest in a serene position, with their arms crossed over their chest.

“He, on the contrary, has very asymmetrical and irregular arms, his face is disfigured, and he appears to still be suffering from the blows that could have taken his life.

“Some researchers suggested a mummification during rigor mortis.”

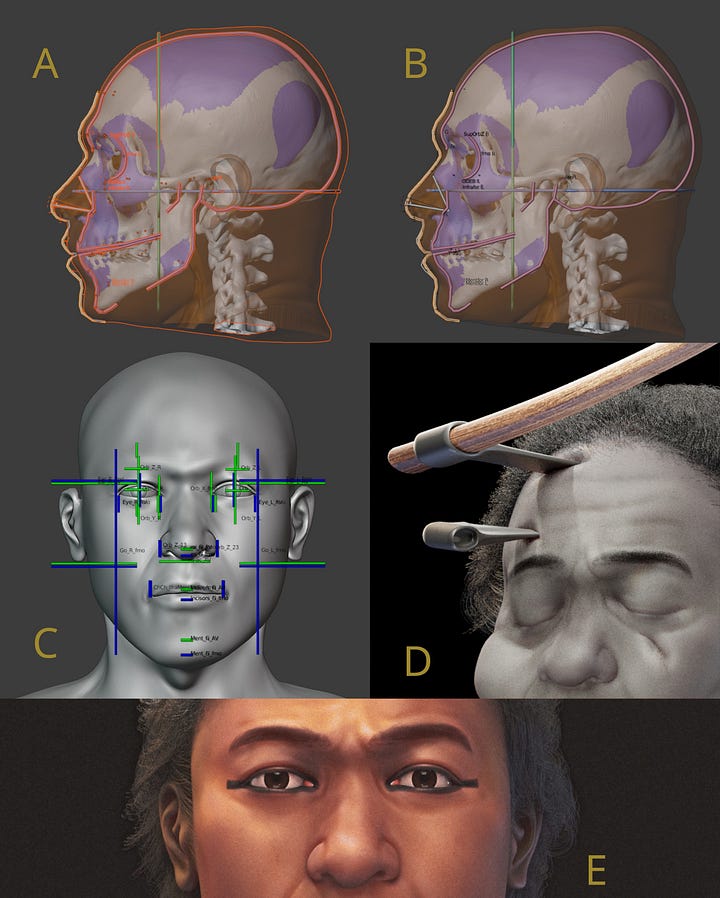

Brazilian graphics expert Cicero Moraes, who recreated the face digitally, said the effort relied on more than 130 years of data – stretching all the way back to 1889.

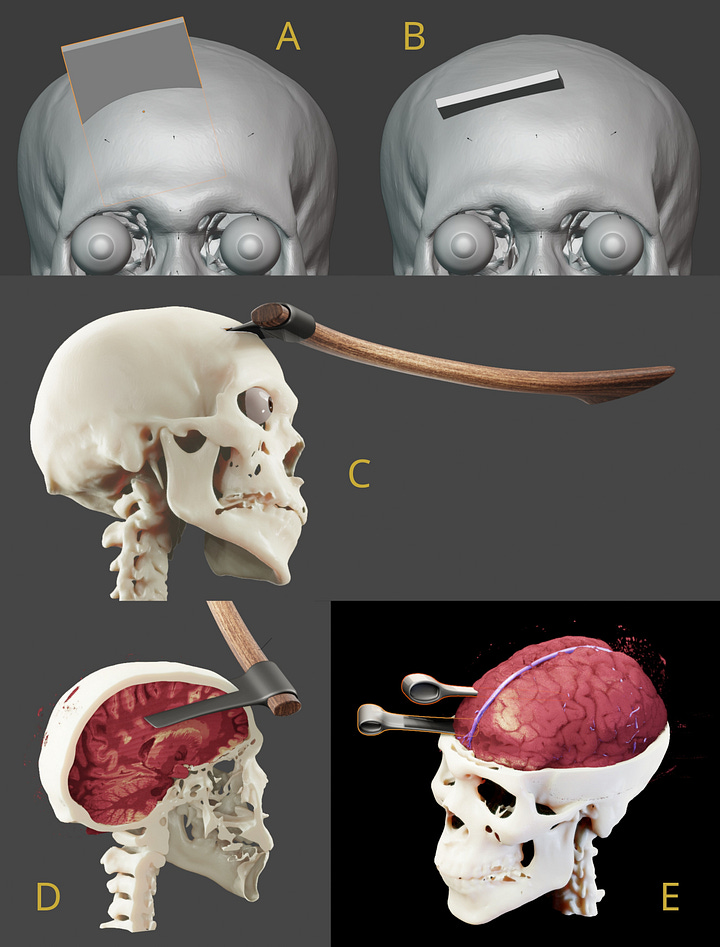

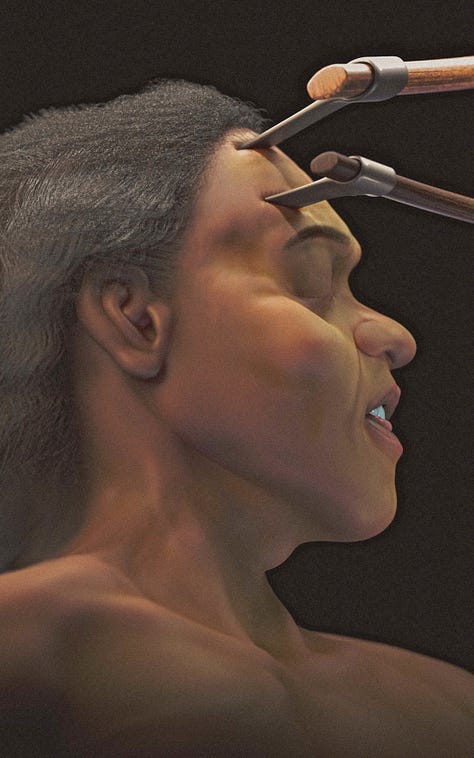

This combination of measurements, CT images, and X-rays allowed them to virtually rebuild the pharaoh’s skull prior to his fatal injuries.

They then used data taken from living people for the reconstruction, warping a donor’s virtual face until it matched the skull, in a process called anatomical deformation.

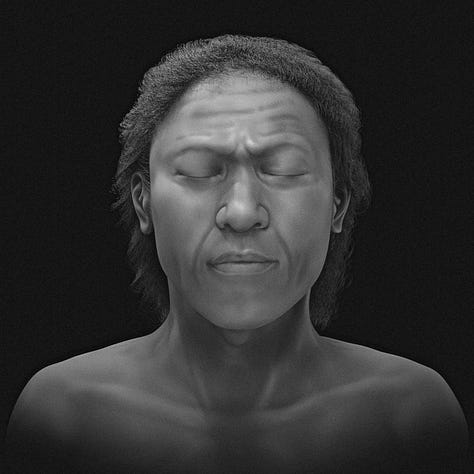

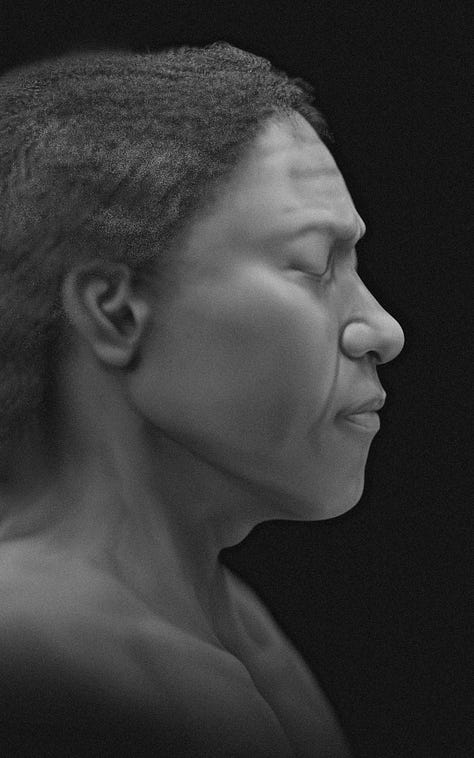

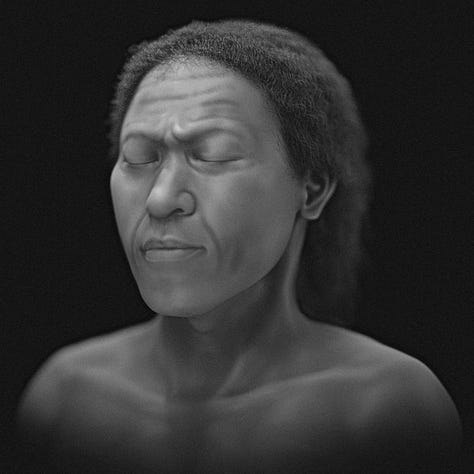

Mr Moraes said: “We created four groups of images.

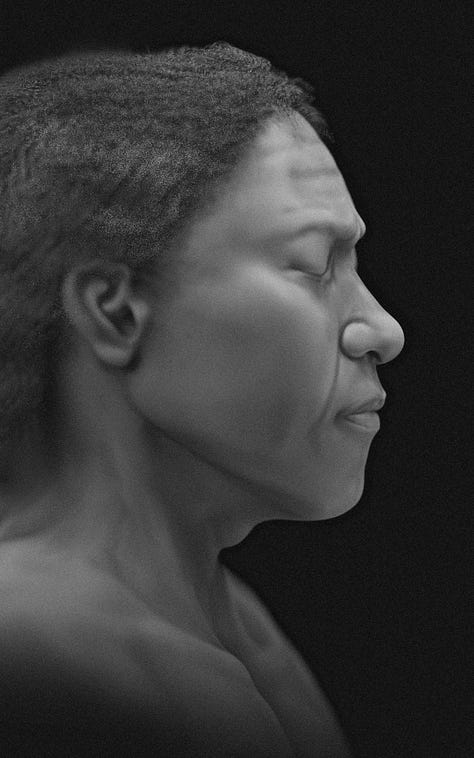

“One group was objective images without speculative elements, with closed eyes and in grayscale.

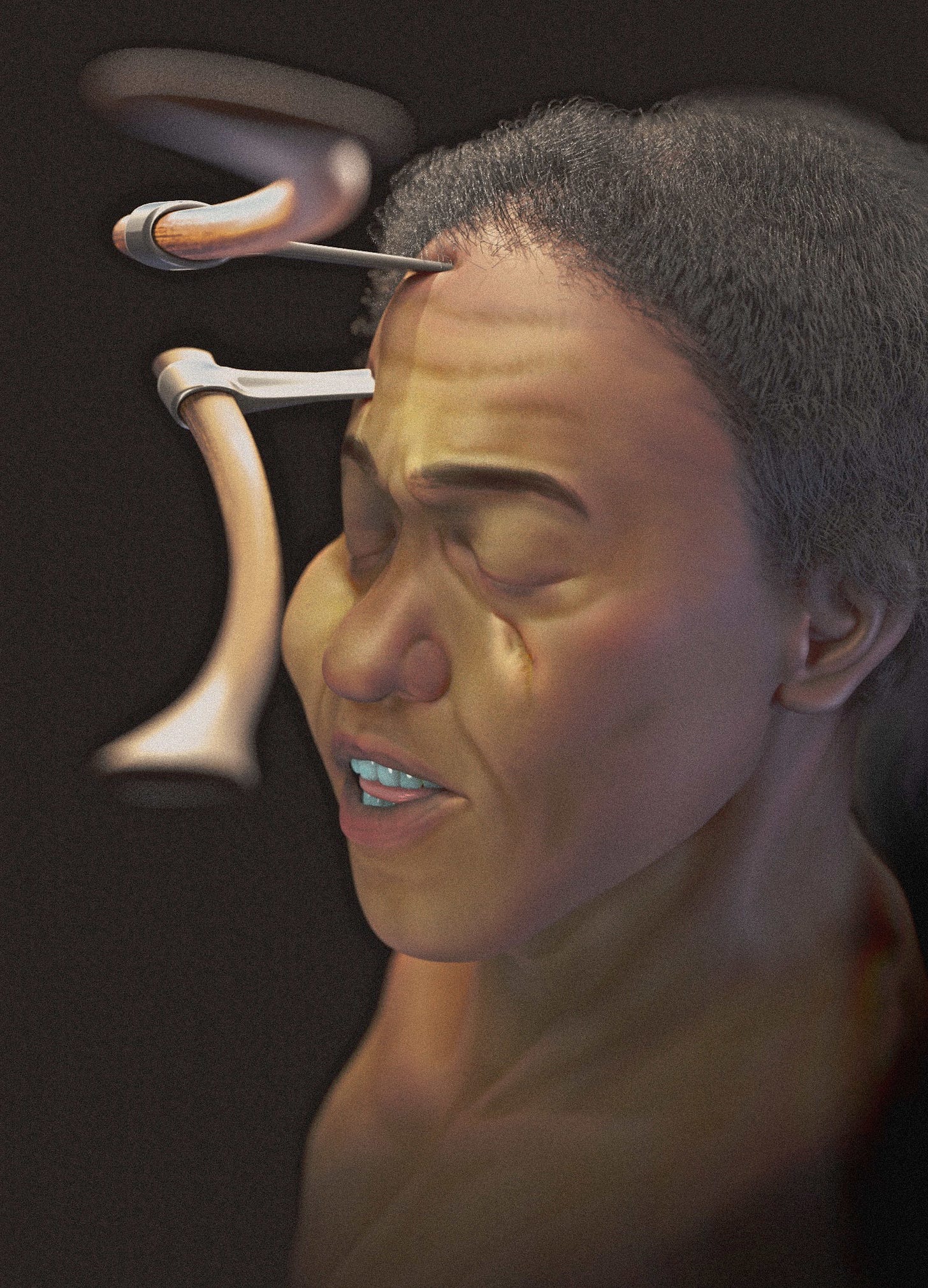

“Another was coloured images, already containing speculative data such as skin colour and eye shape.

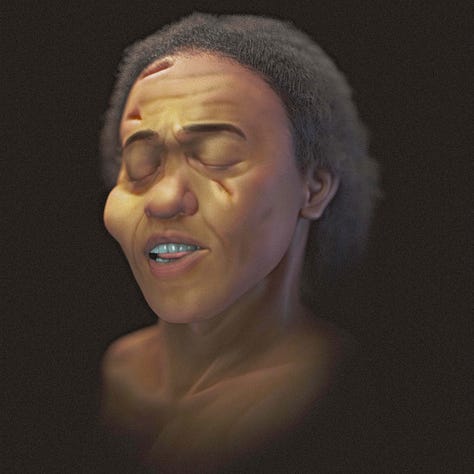

“Finally, two other groups illustrated the potential postmortem appearance of the king – one with only the wounds, and the other with the probable weapons used.”

Dr Habicht said it was the first facial reconstruction ever attempted for the pharaoh.

But he acknowledged that there were some gaps in their knowledge.

He said: “There is no consensus among researchers if Seqenenre was of Nubian – black-African – extraction or not.

“The now-dark skin is not an reliable indicator, as mummies in general tend to darken when they are opened after a long time and exposed to oxygen.”

Even the suggestion that the pharaoh was killed in battle is contested.

Mr Moraes said: “Some authors indicate that he would have been killed during the battle.

“Others suggest he was assassinated during sleep, or that he would have been killed in a ceremonial way by high-ranking individuals from the enemy army.

“What most studies seems to agree on, is that he received one or more fatal blows to the head from axes.

“Whatever happened, the injuries were concentrated on the face.”

He added: “Everything indicates that Seqenenre died a very violent death.”

Dr Habicht said they were the worse pre-death injuries found on any royal mummy, citing a 1980 study by Egyptologists James Harris and Edward Wente.

According to Gaston Maspero, who analysed Seqenenre Tao in 1889, the living pharaoh was tall and slender, with the remains of the muscles in his shoulders and chest suggesting notable vigour.

And though he would not succeed in expelling the Hyksos from Egypt, his son Ahmose I would ultimately finish the job.

Dr Habicht said: “His importance may lay in the fact that he may have started the liberation war – his importance is that of a freedom fighter.”

Mr Moraes said the reconstruction represented a breakthrough.

He said: “We were very honoured to be able to reconstruct his face and show an approximation of what he might have looked like in life.

This project is an achievement in the field of digital technology.

“It shows that it is possible for different research groups to collaborate over decades, in different countries, with different technologies.”

Dr Habicht and Mr Moraes published their study in the journal OrtogOnLine.