Shroud of Turin 'does NOT show face of Jesus'

Bombshell study says image could not have come from a human body

THE face on the Shroud of Turin could not have come from Jesus’ head – and it’s doubtful he ever touched it, an explosive new study suggests.

Marked with a faint impression of a body and face, the artifact is believed by many to be the actual fabric used to wrap Christ’s corpse after his crucifixion.

But its documented history only starts in the mid-14th century, and it’s been a source of scepticism for almost as long, with many dismissing it as a medieval forgery.

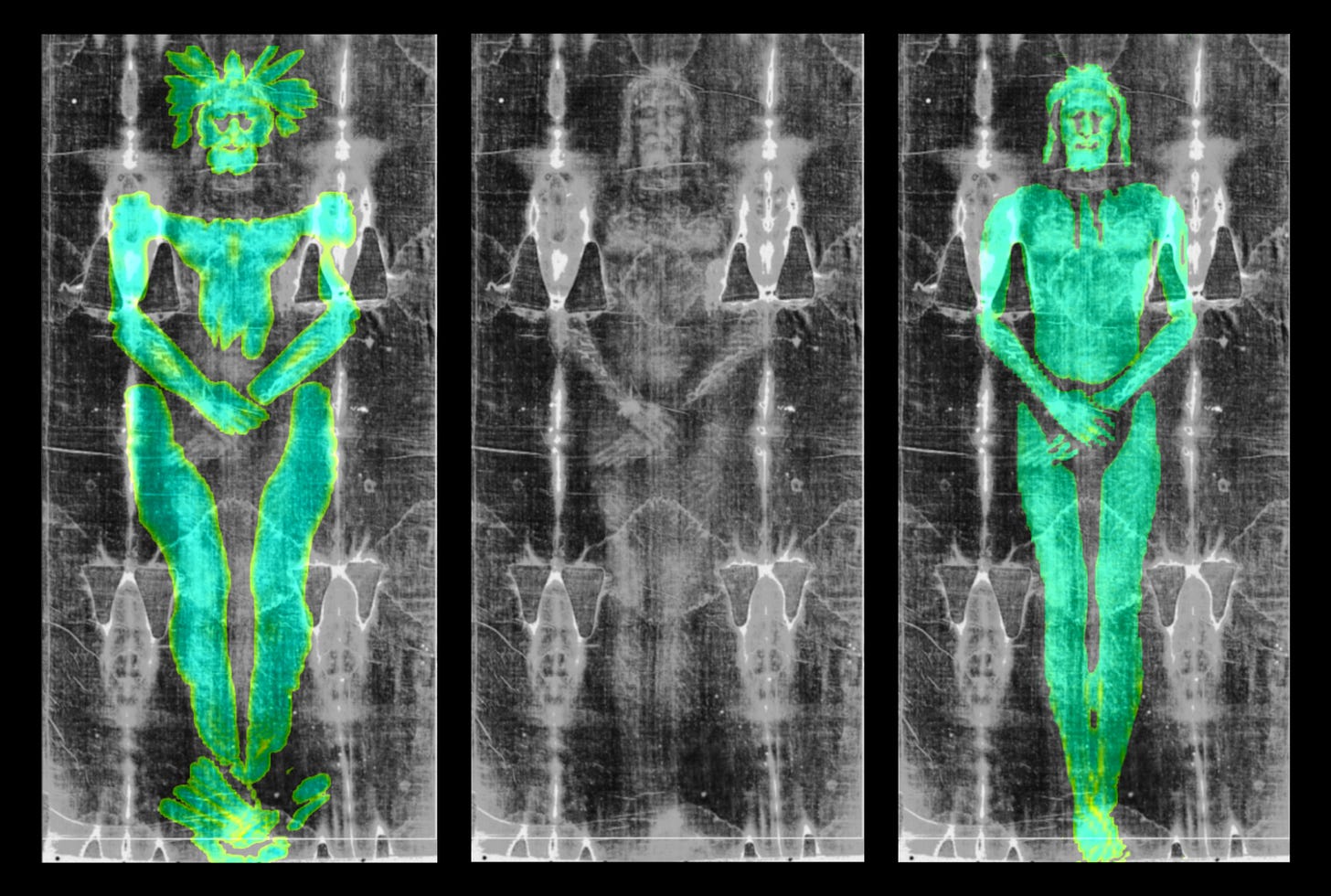

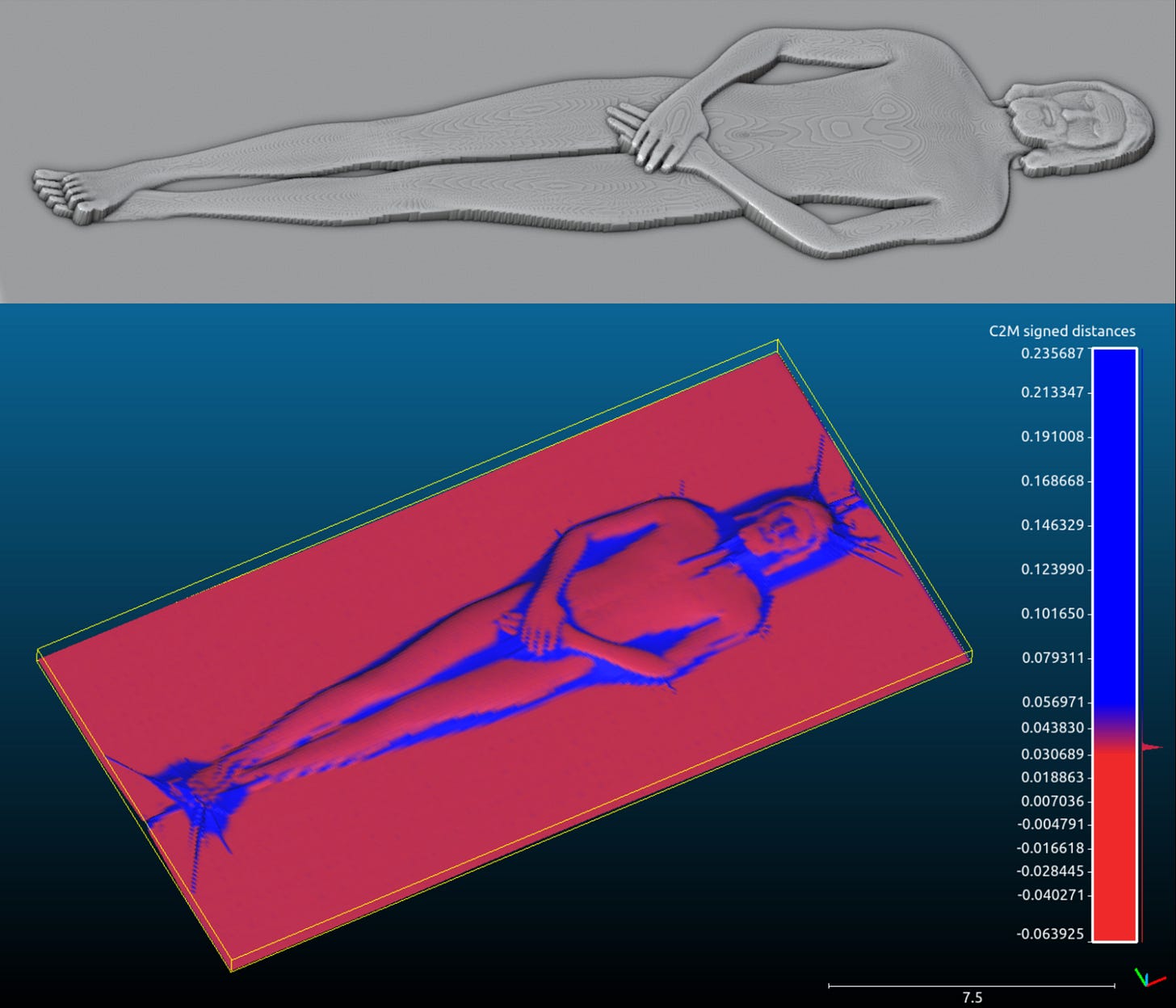

Now a new study has found that the impression on the shroud could not have been made by a three-dimensional human body, but was perhaps from a bas-relief – a shallow carving.

To reach this conclusion, Cicero Moraes, author of the new study, built a virtual simulation in which a fabric was placed over a body in a bid to replicate the famous shroud.

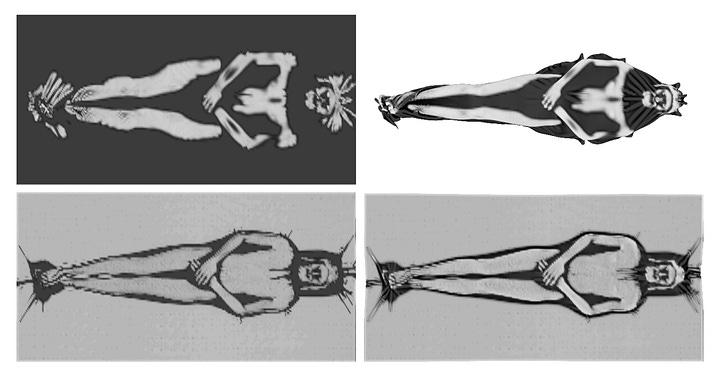

But the virtual fabric, when laid flat, showed “a distorted and significantly more robust image” than that on the shroud, as a result of the change from 3D to 2D.

Only by repeating the process with a bas-relief instead of a body, could an impression similar to that on the artifact be made, the study found.

Mr Moraes said: “The explanation of the differences is very simple.

“When you wrap a 3D object with a fabric, and that object leaves a pattern like blood stains, these stains generate a more robust and more deformed structure in relation to the source.

“So, roughly speaking, what we see as a result of printing stains from a human body would be a more swollen and distorted version of it, not an image that looks like a photocopy.

“A bas-relief, however, wouldn't cause the image to deform, resulting in a figure that resembles a photocopy of the body.”

An image of the impression left by a 3D body shows the striking difference with the shroud.

The scalp and toes splay outward strangely, while large parts of the torso, groin and neck area have not been captured at all, and the likeness in general is very broad.

Meanwhile, the image of the impression left by a shallow bas-relief offers a good recreation of the image from the shroud.

By way of explanation, Mr Moraes offered up the example of the mask of Agamemnon, a gold death mask meant to have been cast from the face of the ancient Mycenaean king.

It seems too wide for a human face, but Mr Moraes said this was actually a normal distortion.

He said: “Any careful adult can test this at home.

RELATED ARTICLES

Do these ruins prove the Bible TRUE?

Does this church hide the 'entrance to the underworld' of Zapotec legend?

Meet the architect of HELL: True face of Dante Alighieri revealed

“For example, by painting your face with some pigmented liquid, using a large napkin or paper towel or even fabric, and wrapping it around your face,

“Then take the fabric out, spread it on a flat surface, and see the resulting image.

“This deformation is known as the ‘mask of Agamemnon’ effect, as it resembles that ancient artifact.”

Mr Moraes, a Brazilian graphics expert, is well known for forensically rebuilding the faces of historic figures from their skulls.

He doubts whether the shroud ever touched the body of Jesus.

“I think the possibility of this having happened is very remote,” he said.

And though he’s reluctant to write off the artifact as a forgery, he believes its qualities are more artistic than historic.

He said: “People generally fall into two camps in the debates.

“On one side are those who think it is an authentic shroud of Jesus Christ, on the other, those who think it is a forgery.

“But I am inclined towards another approach: that it is in fact a work of Christian art, which managed to convey its intended message very successfully.

“It seems to me more like a non-verbal iconographic work that has very successfully served the purpose of the religious message contained within.”

In the 1970s, microscopist Walter McCrone analysed the shroud as part of the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP).

He found that it was painted with pigments of red and vermilion in gelatin, and that there was no blood in the samples, though some of his STURP colleagues disputed his findings.

Radiocarbon testing has also dated the shroud to the 13th or 14th centuries.

But this has been questioned too, with some arguing that the sample may have been from a later repair, or could be in some respect contaminated.

The Vatican itself, meanwhile, has had different positions on the shroud at different times.

In 1390, Pope Clement VII declared that it was not authentic, but was “a painting or panel made to represent or imitate the shroud”.

Then, in 1506, Pope Julius II reversed course and declared it was authentic after all.

Modern popes have spoken of it with reverence, but have generally stopped short of declaring it genuine.

Mr Moraes is publishing his study in the Elsevier preprint repository ahead of formal academic publication.

Read the paper here